Yesterday we travelled to Leiden to visit Museum Corpus and the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave. Leiden is about a 40 minute train ride from Amsterdam Centraal making it a perfect location for a day trip. It is a beautiful historic city filled with museums and stunning heritage places. Right in the city centre is the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, the national museum of science and medicine. If you are even slightly interested in medicine, I would strongly encourage you to visit. On display are some of the most fascinating exhibitions and objects you will ever see.

There is so much to cover in this post. I want to share how we spent our time in the museum and some highlights from each section. To begin, however, here is some museum context.

Context: Museum

The Rijksmuseum Boerhaave is located in the old buildings of the Caecilia Hospital. The hospital opened in 1600 and closed in 1852. After this time, the buildings were used as workhouses. After World War II, the buildings were purchased by the federal government and transformed into a museum. There are two floors of exhibitions to explore including a temporary exhibition space and an entire floor of permanent exhibitions.

The name Boerhaave has come from the Dutch physician Herman Boerhaave. He taught in the hospital during the 18th century and was a early supporter of clinical teaching or teaching students within the hospital. There are a few displays around the museum that tell his story.

Stop 1: Anatomical Theatre

After paying the entrance fee, we walked around to the anatomical theatre for a seven-minute show. This is a reconstructed 14th century anatomical dissection theatre with a model body in the centre. Surrounding the theatre is a medical cabinet of curiosities, containing objects such as wax models of eye diseases, anatomical texts, medicinal jars, and taxidermy animals, to name a few.

Through a series of light projections, the show highlights the history of science and pursuit of anatomical knowledge in the Netherlands. It is a quick introduction to the museum in quite an atmospheric environment. At various stages, the model body in the centre lights up to show the internal organs and blood vessels. I was disappointed that issues, such as the role of colonialism, were not mentioned. This would have added another layer to the presentation and kept it at the forefront of visitors’ minds.

Stop 2: Unseen – Inequality in Medicine

To say I enjoyed this exhibition is an understatement. Right from the start, the introductory panel clearly states the aim of the exhibition; to examine the gender bias in medicine and correct some assumptions and perceptions. There are two disclaimers on the panel. The first is that the language in the exhibition might not always include intersex people. The second warns visitors that there are human remains inside.

After reading the introductory panel, you enter a doctor’s waiting room. It looks exactly like a waiting room with chairs, an area for children to play, and some healthcare posters displayed on the walls. When you are ready, you can head into the main exhibition space to see the doctor. There are three separate themes and sections in the exhibition.

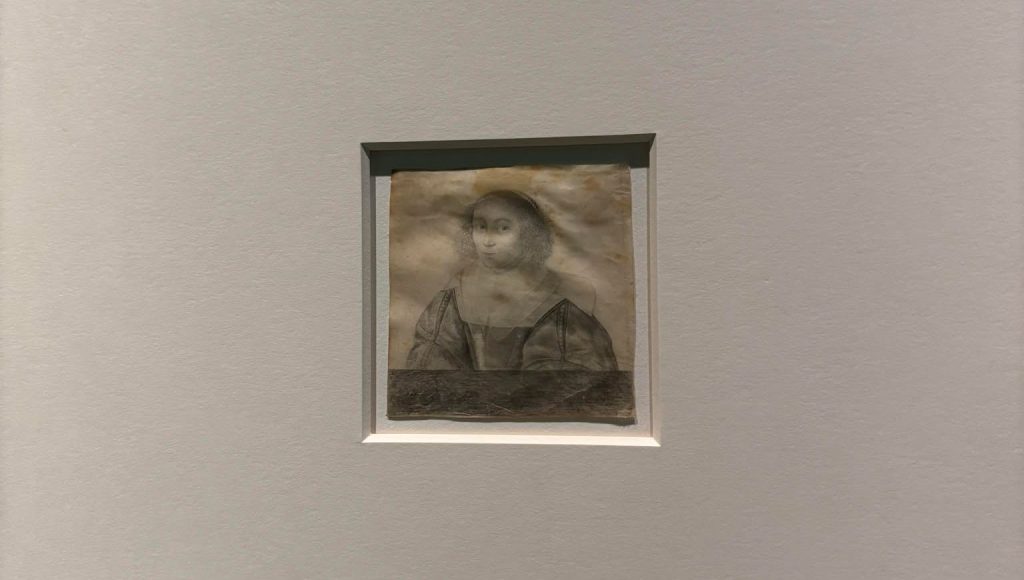

The first is titled unseen. It focuses on how the male body was the only one studied for centuries. There are a selection of texts and models on display including a fragment from a medieval manuscript dating back to between 1400 – 1500. A highlight object in this section is the self-portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman from circa 1630. Although she was allowed to attend medical classes in the 17th century, she had to sit behind a curtain, invisible to the male students. She attended the classes but was not allowed to graduate and become a doctor.

There are models of the female body on display with the point made that these were usually in the form of the anatomical Venus. A woman, laying in bed, pregnant and delicate. According to the object label for the small Venus figurine, it was a collector’s item for male doctors who wanted to show ‘authority over the pregnant body’.

The second section is titled ignored. Here you learn all about how women and gender diverse people have been ignored by medicine and how this often leads to long-term suffering and incorrect diagnoses.

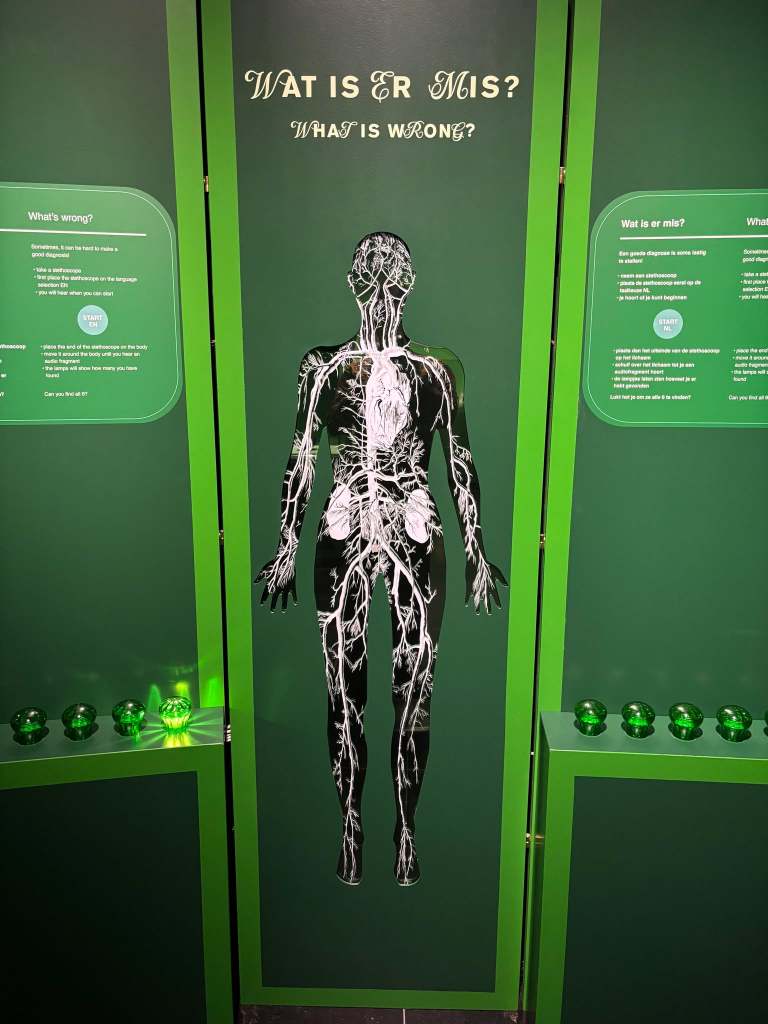

A highlight in this section is an interactive outline of a female body. You are asked to move a stethoscope around the body and listen to find six medical conditions. This, along with other objects in this section, draws visitors’ attention to the fact that women and gender diverse people are far less likely to receive a correct diagnosis when compared to males. This section also addresses intersectionality. For example, the fistula knife of Dr James Marion Sims is on display. He operated on enslaved women without anaesthetic in order to treat a fistula or opening between the vagina and bladder. Many Caucasian women at the time were provided anaesthetic for this procedure.

The final section is titled rebellion. This is where authority is handed back to women and tells the story of how we are fighting for health equality. A highlight object in this section is the booklet by Aletta Jacobs published in 1900. This was sold for a small price to women with limited money so they could learn more about their bodies.

The interactive in this section was a standout for me. Here you can make your own medication box and add stickers with sayings such as ‘beat the bias’ and ‘women are not small men’. Such a powerful interactive and I saw so much engagement by visitors.

Stop 3: Permanent Display

After a break in the cafe, we headed to the top floor to view the permanent display. This covers themes such as the Golden Age, Sickness and Health, and Great Collections. We made it through three of the sections before visitor fatigue set in.

Golden Age

This exhibition covers the Golden Age of Dutch exploration and what contributions were made to science and medicine. There are objects on display such as an original Andreas Vesalius anatomical text from the 1500s.

About half-way through the exhibition there is a digital interactive that is truly a highlight. You lay your arm on a screen which activates the video. Lights are projected onto your arm to make it look as though it is being opened with a scalpel. As surgery is performed, your muscles and bones become exposed. Meanwhile, the screen is telling the story of Vesalius and his dissections at the university of Padua. It is an extremely effective interactive learning tool.

Sickness and Health

This exhibition focuses on the advent of different medical specialities and how they advanced our knowledge of the human body. Similar to a couple of other medical museums we have visited, the exhibition uses patient beds as a way to separate different themes.

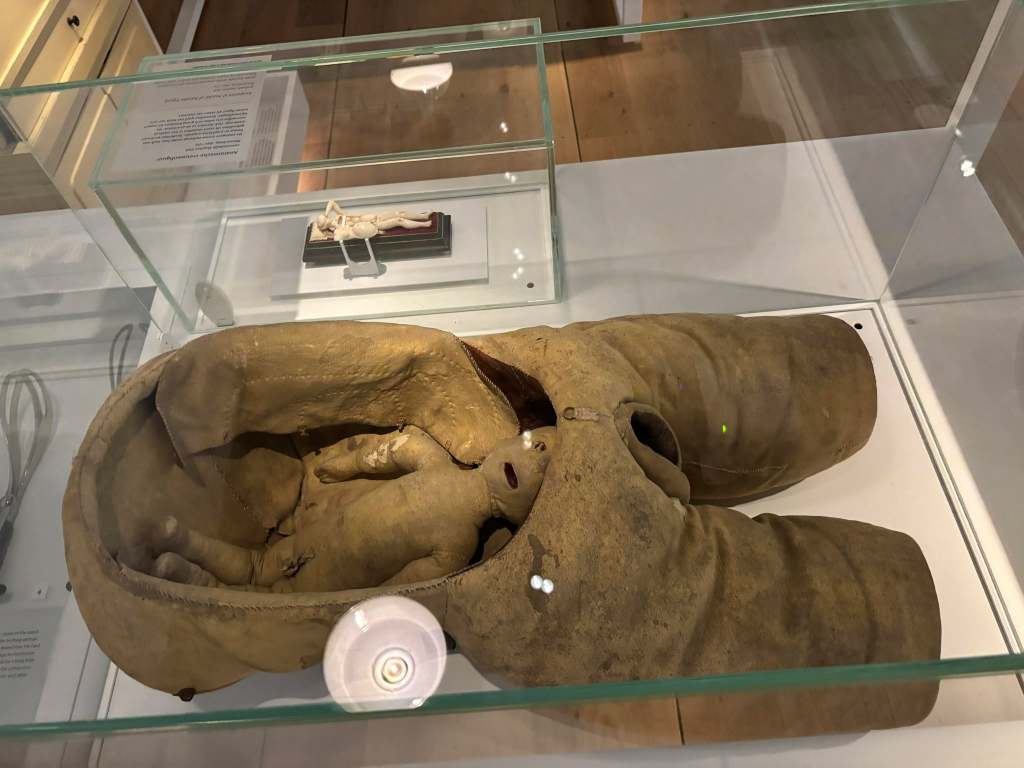

One of the themes is on childbirth and contains this obstetrical training manikin from the 18th century. It was used to train doctors who could use the model to practice birthing techniques. Recent study of such manikins has shown that many actually contain human bone material.

The next room covers the laboratory and how they were critical for studying the human body and, in particular, disease. One of the first objects you see in this space is a travelling medicine chest or materia medica. These compact chests had everything you needed for an in-home, 19th century first aid kit.

Great Collections

The final exhibition I want to cover contains some significant objects from the collection, each with an accompanying digital screen. The objects on display show the future of medicine and raise some critical ethical questions. You can engage with these questions on the digital screens.

For example, on display is an artificial kidney, or early dialysis machine, from the 1940s. The object label describes how the machine works and how it has saved so many lives. The digital screen discusses non-human donors and the ethics behind growing organs in animals or in a laboratory setting. You are asked, would you accept an organ that did not originate from a human?

Conclusion

I have only really skimmed the surface of what is available in this museum. In total, we spent close to three hours here which is almost a record. I would like to revisit in the future and see what we missed. The temporary exhibition, Unseen, is on display until 8 March 2026.

Leave a reply to Rebecca Lush Cancel reply