Disclaimer: This post will contain images of human specimens.

The final stop on my professional development museum tour is London. On the must-visit list was the Gordon Museum of Pathology, Hunterian Museum, and the Wellcome Collection. I spent a couple of hours in the Gordon Museum, a pathology specimen museum attached to King’s College London. It is not open to the public. For this reason, I’m not going to write a post. I am so grateful to the Curator for meeting with me and letting me see the collection.

After touring the Gordon Museum, I boarded a bus and headed to the Hunterian. The last time I visited the Hunterian was back in 2015. I remember the museum being quite overwhelming with hundreds of specimens and limited interpretation. I also remember seeing the skeleton of Charles Byrne and feeling extremely uncomfortable. I was looking forward to returning to this museum and seeing their new exhibition space.

Photography without flash is allowed within the museum but they do request no close-up images of specimens. I will be sharing a couple of images with specimens that will help illustrate my highlights.

Context: Museum

The Museum is named after John Hunter, a surgeon and anatomist who lived in the 18th century. During his life, he amassed a huge collection of anatomy and physiology specimens. The estimate is around 14 000. At the time, this was one of the largest collections of comparative anatomy. Comparative meaning the study of different species. On his death, the collection was donated to the Company of Surgeons, an organisation that later became the Royal College of Surgeons of England. It has remained in their headquarters ever since, located at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, centre of London.

In 2018 the Hunterian Museum closed for a five-year redevelopment. The total cost was approximately £4.6 million. It was great being able to compare how the museum looks today to how it looked in 2015. I will expand on this later but there is a lot more integration of specimens and historical objects, and a lot more opportunities for participation.

Context: Collection

The collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England can be divided into eight categories. These are: Hunterian Collection (comparative anatomy and physiology specimens collected by John Hunter), Hunterian Museum Collection (specimens collected after the death of John Hunter), Odontological Collection, Surgical Instrument Collection, Microscope Slide Collection, Paintings/Sculpture/Furniture, Anatomy Collection, and Pathology Collection.

Together, there is over 70 000 objects in their collection. These cover the history of surgery from around the 17th century to present day. If you are interested, you can actually search and explore the collection online.

Context: Display and Layout

The entire museum is on the ground level of the Royal College headquarters. When you enter the building, straight ahead is a museum information desk. Entrance is free but they do recommend reserving a timeslot to visit online. It is a single path, one-way museum that guides you both chronologically and thematically. There are times when you can visit rooms off to the side of the main path, but it generally doesn’t allow you to deviate too much.

There are ten exhibitions to visit, half of which cover John Hunter and his collection. The other exhibitions are used to introduce visitors to the museum and track the history of surgery and anatomy. The final two exhibitions are dedicated to modern surgery and modern surgical procedures. To finish, there is a small gift shop with some collection-themed and anatomy-themed gifts.

I do want to highlight the Long Gallery, located towards the beginning of the museum. It’s basically how it sounds – a long gallery. Running along both sides are large glass cases displaying some of the original specimens collected by John Hunter. Outside of this space, specimens are integrated with objects in other exhibitions. This is the only space where you will see specimens.

Charles Byrne’s skeleton is no longer on display which is a step in the right direction. Hopefully, his body will one day be repatriated to Ireland.

Highlight: Display of Specimens

My first highlight revolves around the display of specimens in the Long Gallery. As you can see in the image below, each specimen has a light grey plaque with the species it belongs to, name of the organ, and any disease information.

Some specimens have green labels which are used to either highlight something rare or group specimens together. For example, there is a section on tuberculosis and how it affects the body. The green labels group the various organs together under this topic. To the side of the green-labelled specimens is an extra information label. The one I’ve shared below is all about nasal polyps. The label tells the story of Joseph Hayden, a man who visited Hunter in the 1700s to have his nasal polyps removed. He wrote of the pain that was caused by their removal, so his words are included on the label. These stories help to humanise the specimens and add some extra context.

The specimens not in this hall are displayed alongside objects to help illustrate themes or topics. My favourite section focuses on the surgical training of Hunter. There is a small section on how he preserved his specimens – including the tools and chemicals required. The specimens have been selected to show the different preservation techniques.

Highlight: Interactives

Before renovations, I don’t remember there being any interactives or participatory elements. The new exhibitions have a few engagement opportunities. I had two favourites:

1: The interactive digital tables that teach the history of surgery and the human body systems.

2: Accessibility additions such as the touch plates of the Evelyn Tables. These are anatomical preparations from the 1600s including blood vessels and nerves that were removed and pasted onto wooden boards.

Highlight: Patient Inclusion

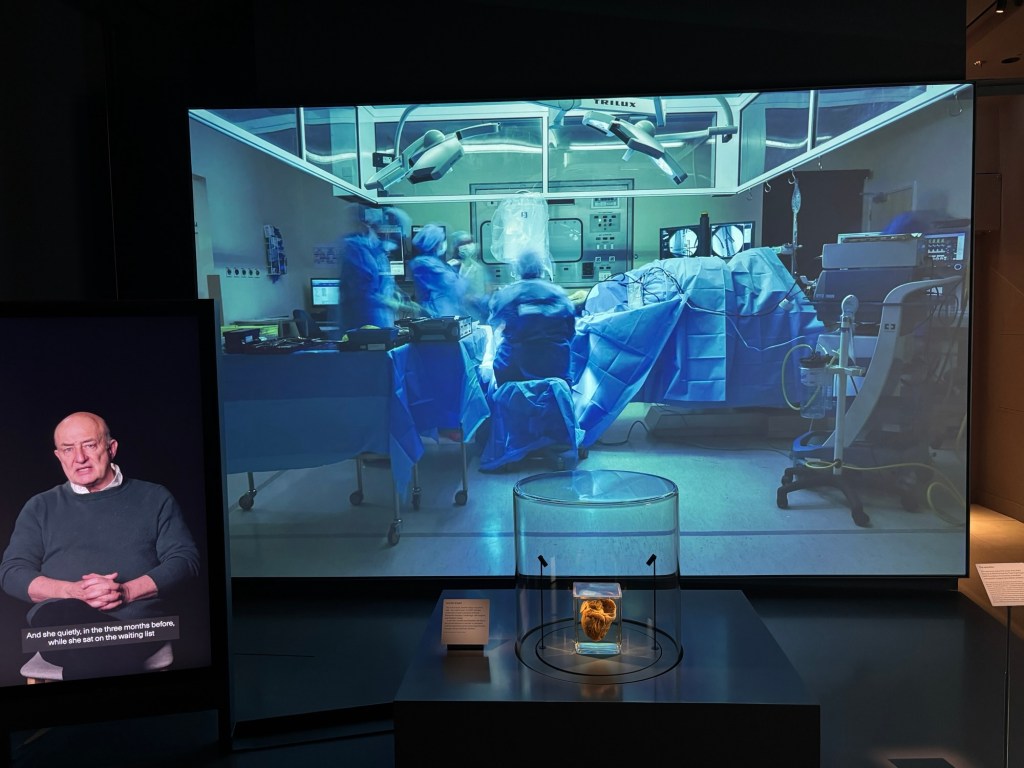

The final highlight for me is the inclusion of patient voices. In the final room, you can sit and listen to patients tell their healthcare stories. This is a great addition to the space and you leave feeling multiple perspectives have been included in the museum.

Conclusion

Overall, the renovations have transformed the museum into a more engaging experience that includes additional perspectives. The display of specimens is, to me, more educational than in the past. I enjoyed reading the stories and seeing the variety of specimens available. One day, I hope they have an empty case, displaying the story of Charles Byrne and how important it is to continue ethical discussions surrounding these collections.

Leave a comment